CALCIUM PHOSPHATE

The key technology to regenerate your bones

[1]

- Setting reaction of α-TCP: 3(α-Ca₃(PO₄)₂) + H₂O → Ca₉(PO₄)₅(HPO₄)OH; α-Ca₃(PO₄)₂ = α-TCP; Ca₉(PO₄)₅(HPO₄)OH = CDADissolution: α-TCP particles dissolve in water, releasing Ca2+ and PO43- ions.

- The supersaturation of the medium following the dissolution of alpha-TCP (alpha tricalcium phosphate) leads to the nucleation and growth of CDA (Calcium Deficient Apatite), an osteoconductive and osseointegrative structure resembling bone mineral.

[2]

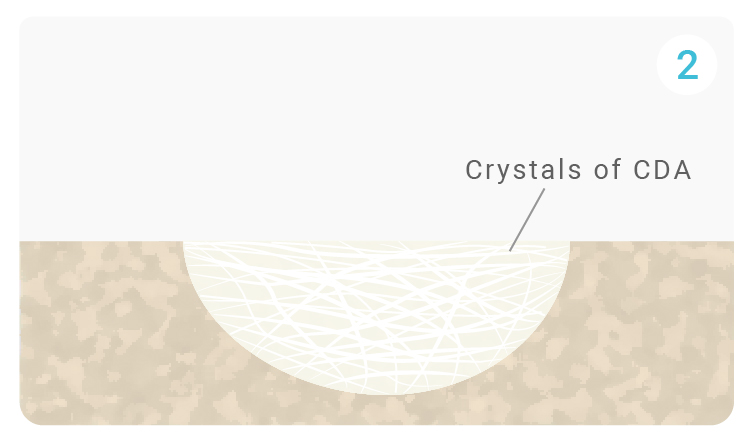

Growth of CDA crystals following nucleation, forming a network of overlapping crystals to create a solid matrix.

[3]

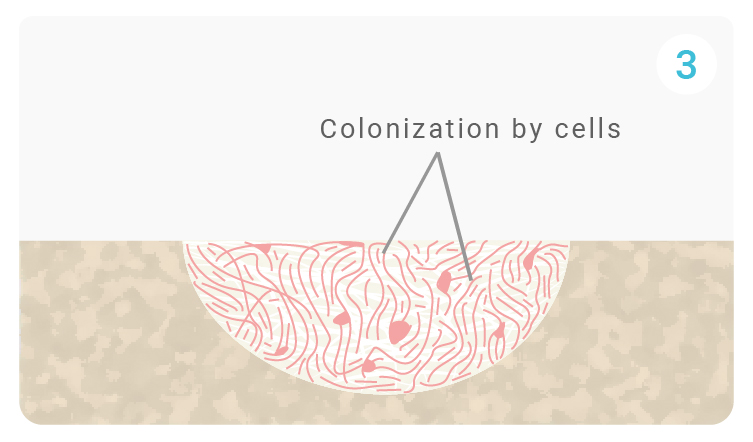

The porous matrix of QS composed of CDA improves fluid and ion exchange at the surface of the biomaterial as well as the adsorption of proteins that attract bone cells. Through the pores, osteoclasts colonize QuickSet and adhere to its surface via their pleated membrane. They release acids and enzymes that promote the resorption of QuickSet. Growth factors activate M2 macrophages to promote wound healing and initiate the migration of progenitor cells to the site.

[4]

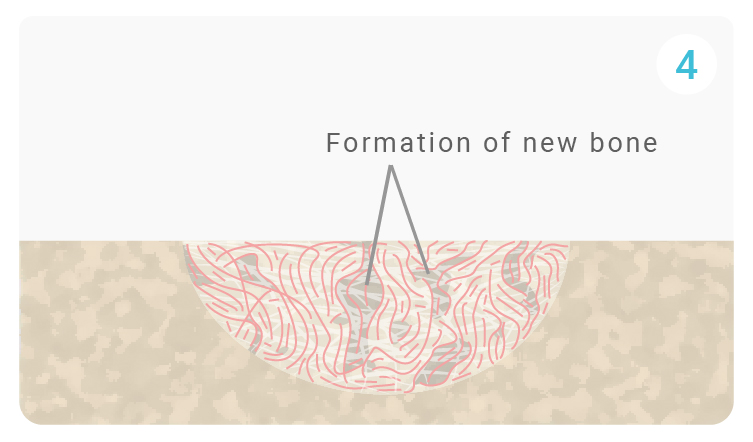

Osteoblasts, progenitor cells, penetrate QuickSet through the pores and attach themselves to the resorption lacuna. These cells generate and deposit extracellular matrix (ECM) components, mainly type I collagen, the main protein component of bone.

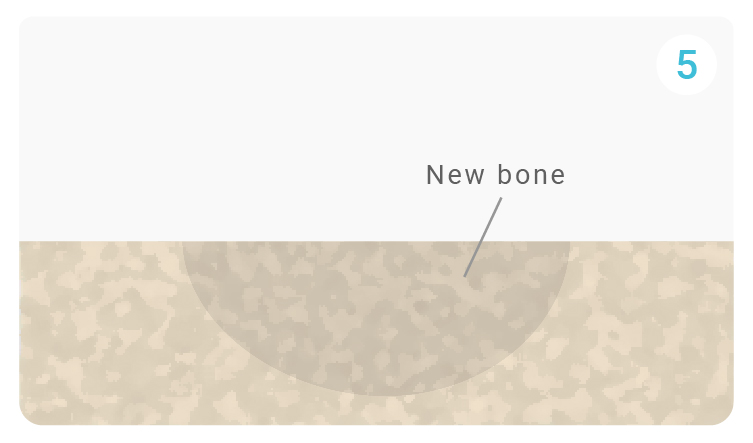

[5]

Following these reactions, bone growth continues as newly recruited cells continue to function and facilitate tissue growth and repair. Quickset continues to degrade and be converted into extracellular matrix.

HISTORY

Calcium phosphate plays a central role in the field of biomaterials as it is chemically and structurally similar to the mineral phase of human bone. Long before being used as a synthetic biomaterial, calcium phosphate was identified as the main inorganic component of skeletal tissue, primarily in the form of biological hydroxyapatite.

In the first half of the 20th century, researchers studying bone chemistry established that bone mineral is not an inert structure, but a dynamic, calcium phosphate–based material constantly remodeled by the body. This fundamental discovery laid the groundwork for the idea that a synthetic material mimicking bone mineral could be accepted by the human body rather than rejected.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, as orthopaedic and reconstructive surgeries increased, clinicians faced a major limitation: the lack of safe and abundant bone graft material. Autografts were limited in quantity and associated with donor-site morbidity, while metals and polymers often failed to integrate with bone. This challenge prompted researchers to revisit the chemistry of bone itself.

Inspired by the natural composition of skeletal tissue, scientists began synthesizing calcium phosphate ceramics, primarily hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate. Early work led by pioneers such as Klaas de Groot and Robert Z. LeGeros demonstrated that synthetic calcium phosphate materials were biocompatible, non-toxic, and capable of supporting bone growth.

One of the most decisive moments came when porous calcium phosphate implants were placed in bone defects during preclinical and clinical studies. Rather than being encapsulated or rejected, the material allowed bone cells to migrate along its surface and through its pores. Researchers observed a phenomenon that would later be defined as osteoconduction: bone grew directly on and within the calcium phosphate structure, gradually anchoring the implant to the host tissue.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, it became clear that not all calcium phosphates behaved the same way in vivo. Hydroxyapatite proved to be highly stable and slowly resorbable, while β-tricalcium phosphate exhibited faster resorption, making it suitable for applications where gradual replacement by natural bone was desired. This led to the development of biphasic calcium phosphates, combining stability and controlled resorption to better match physiological bone healing.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, calcium phosphate substitutes were progressively validated in orthopaedics, traumatology, maxillofacial surgery, and dental applications. Their ability to act as a temporary scaffold for bone regeneration, without inducing adverse immune reactions, marked a turning point in regenerative medicine. Unlike metals or inert polymers, calcium phosphate materials were no longer perceived as foreign bodies, but as biofunctional extensions of bone itself.

By the early 21st century, calcium phosphate had become one of the most widely studied and clinically used bone substitute materials worldwide. Thousands of scientific publications confirmed its safety, versatility, and regenerative potential. Today, calcium phosphate remains a cornerstone of bone regeneration strategies, continuously refined through advances in porosity control, mechanical performance, and biological interaction, with the shared objective of restoring — and ultimately regenerating — functional bone tissue.